In this tutorial, I'll introduce you to Dart and how to start using it. In the course of the article we'll build a simple JavaScript-based image marquee without writing a single line of JavaScript - just Dart.

Note: This tutorial was originally published in March 2012, as a freebie for our Facebook fans. Since Activetuts+ has now shut down, we're making it free to all readers.

Project Preview

We will be building the following simple marquee, a screenshot of which is shown below. Click on the image to launch a working example of the project.

Step 1: Install the Dart Editor

Let's get started building out little marquee. From here on out, we'll be much more hands-on, and I'll take the time explain the new stuff along the way.

First things first; we can write Dart in any old text editor, really, but the most convenient way to get started and to immediately run your project in a browser (via JavaScript compilation) is to install the Dart Editor.

Head to http://www.dartlang.org/docs/getting-started/editor/, which should automatically detect your OS and present you with the appropriate download link. It's not a small download, around 65 MB at this writing, so get it started before continuing to read.

The Dart Editor is rather bare-bones. It's built on Eclipse, and I hope that eventually it will be offered as an Eclipse plug-in for those with an existing Eclipse installation. But for now, it's a self-contained Eclipse modification that does Dart and not much else.

It offers a few of the features that Eclipse workspaces typically offer, such as language-aware completion. The big advantage it brings, though, is a fairly simple way to start and run a Dart project.

Once the download completes, extract the ZIP file and you'll have a dart folder. You can place this wherever you like; I've moved mine to my Applications folder.

Step 2: Create a Dart Project

Let's open up the Dart Editor application. You'll find it just inside that dart folder you just unzipped.

Once it launches, you'll be presented with a "Welcome" page, which provides a jumping-off point to some sample projects. These are certainly worth taking a look, but we'll skip past them for now and first get a little more familiar with the language.

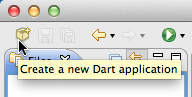

Go to the File menu and choose New Application... or click on the top-left icon in the toolbar:

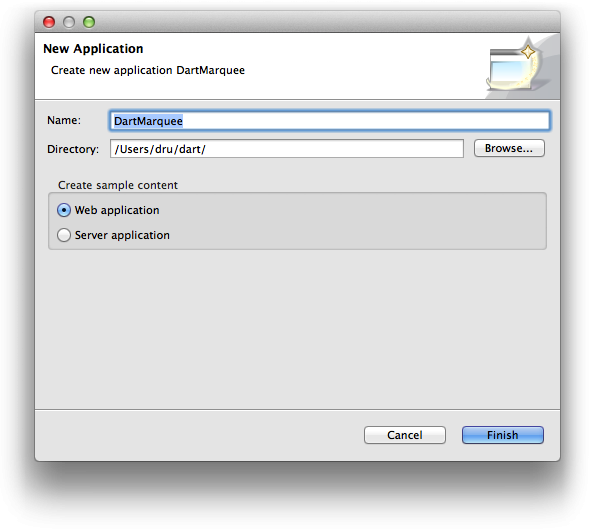

In the resulting window, enter a name for the project (I'm using DartMarquee). It will want to store the project in a folder named dart in your home directory, but you can change that by clicking on the Browse... button. Note that whichever folder you choose, Dart Editor will create a new folder in the selected folder, using the name you've given for the project. Inside of that there will be a few files created for you, also using the name of the project you supplied.

Also be sure the "Web Application" is selected, not "Server Application."

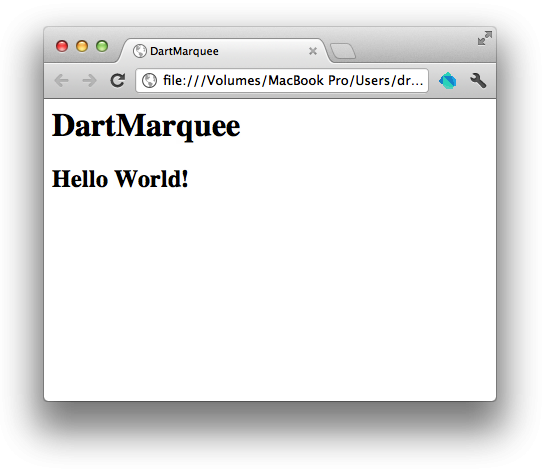

Step 3: Run the Hello World Example

The default project created for you is a simple Hello World example. You may as well see what happens before we start building our (slightly) more complicated project. Run the application by either choosing Tools > Run from the menu, pressing Command-R (Mac) or Control-R (PC), or by clicking on the green "play" button in the tool bar:

You may expect this open up in your default browser, but - surprise! - Google's Chromium browser will open (not to be confused with Chrome; Chromium has a blue-ish monochrome icon, not Chrome's colorful icon). Chromium has built-in support the the Dart language.

This is not the process I mentioned earlier where Dart files are compiled into JavaScript; this is the Dart VM running regular Dart code, which is cool, but not terribly useful for those of us currently building JavaScript applications. We'll make the project compile to JavaScript next.

Step 4: Add a JavaScript Launch

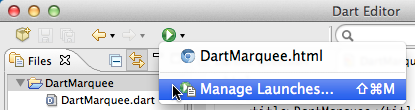

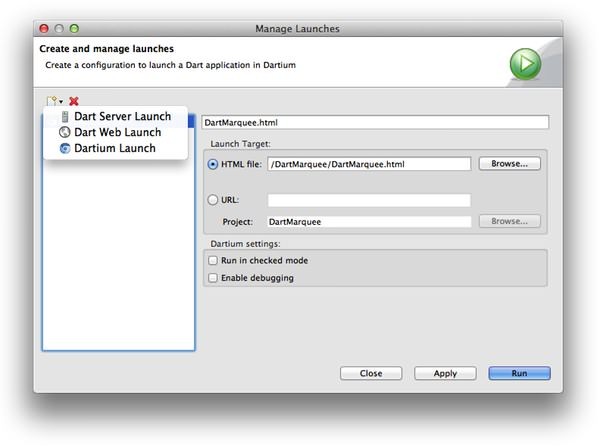

If you change the run settings, then we can get Dart to compile to JavaScript. To change these settings, choose the Tools > Manage Launches... menu, press Command-Shift-M (Mac) or Control-Shift-M (PC), or click and hold the downward arrow next to the Run tool bar button, and choose Manage Launches... from the pop-up menu.

In the window that appears, you'll see the default launch created for you, which has the Chromium icon. To create a new launch, click on the new document icon, which will display a pop-up menu.

Choose Dart Web Launch from the menu. In the top field at the right, give it a meaningful name, like DartMarquee JS or something to designate that we're going for a JavaScript rendition in another browser.

Under Launch Target, click Browse... next to HTML file:. A window will open that presents all (one) HTML files present in your project. Click on DartMarquee.html and then click OK.

Under Browser you can choose to leave the default checked, or uncheck that option and then specify a browser with the Select... button. The browser choice shouldn't matter too much, although I will be using some CSS3 tricks so a modern browser would be ideal.

Click Apply and then Close.

Now run the project again, but this time be sure to do it by clicking and holding on the Run tool bar button, and then selecting your new launch target. You should now get the same Hello World application in the browser of your choosing, which will be using JavaScript compiled from Dart. In fact, you'll see a new file show up in your file list: DartMarquee.dart.js. This is the compiled JavaScript file.

Now that you've run the new launch once, future Runs will remember this decision and launch the JavaScript version.

But we're not done yet. The HTML file is set up to include the Dart file, along with another JavaScript file that interprets Dart files in the browser (which is super-cool, but not the best for production applications). We need to edit the HTML file to use the compiled JavaScript file, not the Dart files.

Step 5: The HTML

Your new project should open with DartMaquee.dart in the main editor area. We'll get to that soon enough, but let's get our HTML page set up. Double-click on DartMarquee.html in the file list on the left, and it will open in a new tab in the editor.

Dart Editor is really only aware of the Dart language, which is too bad. You'll notice that the HTML file opens without any syntax coloring or intelligence about the language. It's good enough for our purposes now, but feel free to open this file (and any other non-Dart file) in the text editor of your choosing. We won't be spending too much time in non-Dart files, so I'll just be editing them in Dart Editor for this tutorial.

The body markup is not what we want, but first let's update those <script> tags as mentioned in the last step. You can delete the first <script> tag altogether; that's the once that includes the Dart file directly. Delete this line:

<script src="http://dart.googlecode.com/svn/branches/bleeding_edge/dart/client/dart.js"></script>

(Hint: line numbers aren't enabled by default, but that's one of the few options available under Preferences).

The script is the in-browser runtime for Dart; one pretty nifty feature is that you can write Dart without compiling it to JavaScript, and have browsers run it anyway. You just need to include dart.js. Of course, this makes for some extra overhead and impacts performance. Pretty cool trick, though.

Now let's change the remaining <script> tag to load our compiled JavaScript file. Change this:

<script type="application/dart" src="DartMarquee.dart"></script>

To this:

<script src="DartMarquee.dart.js"></script>

If you like, run the project again, and use the developer tool to ensure that the JavaScript file is loading, and the other two are not.

Now, change that <h2> tag into a <div>, and give it an id of marquee.

<div id="marquee"></div>

You can leave the <h1> if you like; sometimes it's nice to have page identification.

Finally, we need to link to a CSS file (which we'll create in the next step). In the <head> add a <link> tag:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="DartMarquee.css">

The application will not work, because we've removed the <h2> that was targeted by the Dart code, not to mention that we still need a CSS file. Let's do that next.

Step 6: The CSS

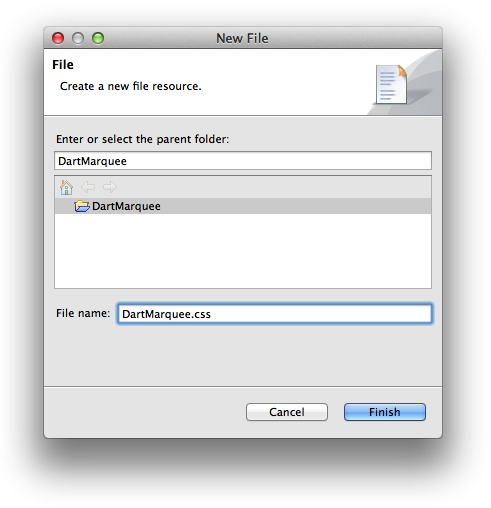

We've linked to a non-existent CSS file, so let's address that. In the Files area of Dart Editor, right-click, and choose New File: from the menu (you can also find New File... in the File menu).

In the resulting window, you may need to ensure that the DartMarquee project is selected in the middle area. Then enter DartMarquee.css for the file name, and click on Finish.

This file will be ready to edit in the main editor area, but as with HTML files, CSS files aren't intelligently supported with syntax by Dart Editor. Feel free to do your CSS editing in your preferred text editor. Or, since we're really not here to delve into the CSS, just copy and paste form below into Dart Editor:

#marquee {

width: 600px;

height: 400px;

background-color: #111;

}

.mainImage {

height: 300px;

background-color: #666;

position: relative;

}

.mainImage img {

display: block;

position:absolute;

left: 0px;

top: 0px;

-webkit-transition: opacity 0.6s ease-out;

-moz-transition: opacity 0.6s ease-out;

-ms-transition: opacity 0.6s ease-out;

-o-transition: opacity 0.6s ease-out;

transition: opacity 0.6s ease-out;

}

.mainImage img.fade_away {

opacity: 0;

}

.thumbContainer {

height: 100px;

background-color: #DDD;

}

.button {

width: 100px;

height: 100px;

background-color: #eee;

position: relative;

float: left;

}

.button .border {

width: 90px;

height: 90px;

position: absolute;

opacity: 0;

border: 5px solid orange;

-webkit-transition: opacity 0.3s ease-out;

-moz-transition: opacity 0.3s ease-out;

-ms-transition: opacity 0.3s ease-out;

-o-transition: opacity 0.3s ease-out;

transition: opacity 0.3s ease-out;

cursor: pointer;

}

.button:hover .border {

opacity: .5;

}

.button.selected .border {

opacity: 1;

}

Again, we're not here to discuss CSS. I'll point out that I'm using CSS3 transitions for the button hovers and the main image changes. Otherwise, it should be fairly straightforward.

Run the project one more time, or simply reload from the browser; at this point there won't be any JavaScript to re-compile. If you run from Dart Editor, be sure to switch back to the HTML or Dart file; Dart Editor doesn't know what to do when you "Run" from a CSS file.

You should see a large dark rectangle. Doesn't look like much yet, but you're on the right tack.

Step 7: Preparing the Images

One more housekeeping task, and that's to make our images readily accessible, so that we can see them when we're ready to write that code.

In the download package, you'll find a folder named images. Copy or move this folder from the download archive to your project folder, so that's sitting at the same level as your other files. You'll probably need to use the Finder/Explorer for this task, as Dart Editor doesn't (yet) support importing or drag-and-drop of existing files. They'll show up in your file list once you get them in place, though.

Now we can get into some Dart code. That's next!

Step 8: The main() Function

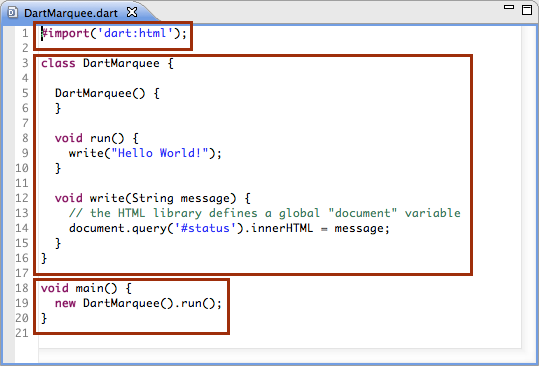

Open up the DartMarquee.dart file in the editor. You'll see three main blocks of code:

The third block is the main function, and this is a required part of your Dart project. Dart will look for this function as an entry point to execution. Contrast this with JavaScript where scripts are simply executed from top to bottom. You can certainly replicate this methodology in JavaScript, but the key difference is that you don't have to, and if you do you have to call main() yourself; in Dart, it's expected that you have the main function, as it will be called for you once Dart in ready to begin execution of your application.

This won't be a foreign concept to you if you've programmed in C or Java, or even in ActionScript 3 and used the Document class. The nice thing about it is that there is a standardized, expected place to begin the execution of your code.

Step 9: Classes

Dart brings with it proper classes, which you may end up preferring to JavaScript's class-ish-ness prototype system. Take a look at the second block of code in DartMarquee.dart. This is the meat of the program right now, and is a class with two methods declared. We'll be ditching a large part of this code. We'll get into the syntax as we go, but for now, hollow out this class so that it looks like this:

class DartMarquee {

DartMarquee() {

}

}

What this leaves is the class declaration and the constructor. The class declaration begins with class, which is followed by the name of the class. That this class is named DartMarquee is purely a function of the template used in the application creation process in DartEditor. It's important to know that just because this file is named "DartMarquee.dart" does not mean that there has to be a class name DartMarquee inside. We're not going to change it, because it makes sense, but Dart is like PHP or Ruby in that you can put as many class definitions as you like in a single file, and the naming doesn't need to match the file name (as it does in ActionScript).

The class definition is then contained between the curly braces. Inside of that, we have a constructor. This is a function that is run when a new object is instantiated from this class. Typically one puts set-up code in a constructor. Note that the name of the constructor needs to match the name of the class, otherwise it's not a constructor, and is a regular method instead.

Everything else you add to a class should go in between the two curly braces denoting the class.

You'll notice that back in the main function, a DartMarquee object is instantiate with this line:

new DartMarquee().run();

This should look like object-oriented JavaScript. The .run() then calls the run method on the newly-created object. We just removed that method, so go ahead and change that line to this:

new DartMarquee();

Step 10: Imports

Something I'm pretty excited about with Dart, as someone coming from JavaScript, is the ability to easily import and use other code into your project. The first block of our default code uses a single import statement:

#import('dart:html');

This imports a built-in Dart library, one that deals specifically with HTML pages and giving us access to DOM manipulation functionality. We'll be importing other libraries as we need them, including one that we'll write ourselves.

When our Dart project is compiled to JavaScript, all of the disparate Dart code is converted and concatenated into a single JavaScript file. It's smart enough to not include the same library twice, so you can import libraries from other files and not worry about them conflicting with or duplicating code in the final product.

Our DartMarquee.dart file should look something like this now:

#import('dart:html');

class DartMarquee {

DartMarquee() {

}

}

function main() {

new DartMarquee();

}

Step 11: Add a Property to the Class

Let's finally write code. We're going to add a target property to the DartMarquee class, so that the main HTML element that we're referencing is handy within the class.

Just after the class declaration, and before the constructor, add a property like so:

class DartMarquee {

Element _target;

DartMarquee() {

}

}

Notice the syntax here: instead of var, we use a datatype to both declare a variable and give it a datatype all at once. This syntax is reminiscent of C and Java. The name of our property is _target, and the line ends with a semi-colon. You'll find Dart much less forgiving about missing semi-colons.

An interesting thing about Dart type system is that it's optional. If you specify a type, Dart will do what it can to adhere to typing rules. But we could also opt to leave typing off by writing that property like this:

var _target;

Dart will then not attempt to keep your types safe; you'll have a dynamically-typed variable just like in JavaScript. What's even more interesting than the fact that it's optional is that you can mix strong and dynamic typing in the same code.

Personally, strong typing is one of the things that draws me to Dart, as it's helpful to have that kind of accountability. This will be the last time I mention dynamic typing in Dart.

We're not done with that property yet. This is an important property, so let's set it in the constructor.

class DartMarquee {

Element _target;

DartMarquee(this._target) {

}

}

This may look a little unexpected. This is a Dart idiom; it's so common for a constructor to receive arguments, and then simply use the constructor's body to stash those values into properties, that Google created a shortcut.

Normally, a method parameter looks like you'd expect it to: any variable name will do, but not something that looks like a property on another object. These parameters are normal parameters like you're used to; they're available by name within the body of the method.

This new syntax, however, will go ahead and assign the value passed in to this parameter to the property designated by the parameter name. In other words, the code above is identical to this code:

DartMarquee(target) {

this._target = target;

}

Only we don't have to write that boilerplate of a line.

Note that this shortcut is only available in constructors.

Step 12: DOM Queries

Now that we have a target property set up, we need to give it a value. Back in the main function, we need to select the marquee <div> and pass it in to the constructor.

Dart provides a method to find HTML elements by CSS selection, much like jQuery or any of the popular JavaScript libraries do. This is provided by that dart:html library imported at the top of the file, which also provides a top-level document variable which gives us global access to the HTML document.

Update the main function to look like this:

void main() {

new DartMarquee(document.query('#marquee'));

}

It's that simple: if you've used jQuery (or another library), this should be rather familiar. Simply call document.query and pass in the selector. Dart does the rest.

Step 13: Console Logging

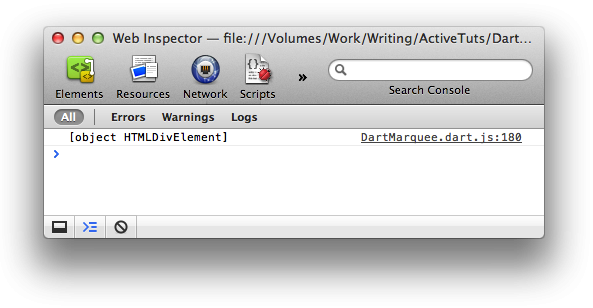

If you've developed with JavaScript, chances are you've made heavy use of console.log to test and verify your code. Dart provides a print function that, when compiled to JavaScript, turns in to a call to console.log. Let's try it out, and test our project so far at the same time.

In the DartMarquee constructor, let's print the _target property to make sure it's being set.

DartMarquee(this._target) {

print(this._target);

}

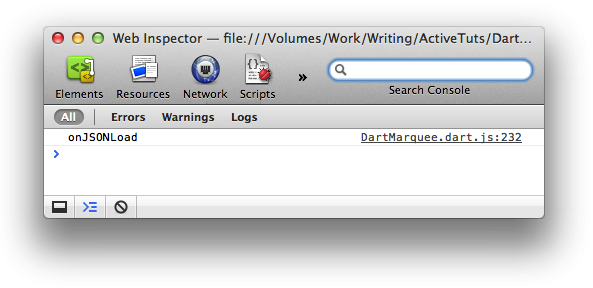

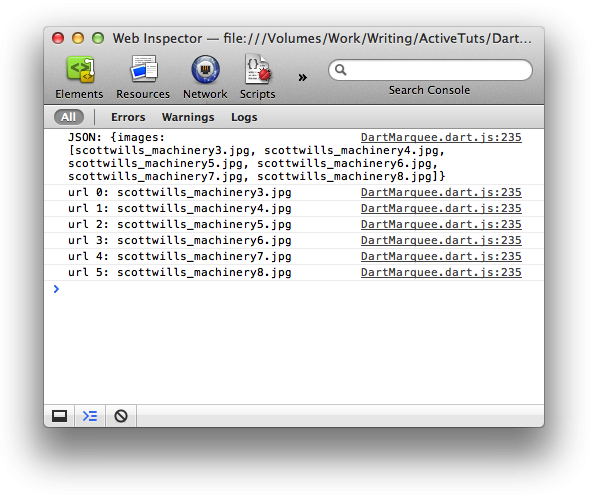

And hit Run. In your browser, open up your console and you should see something like this:

Note that at the time of this writing, there is a bug with the Dart Editor that generates a warning stating that "print" is not a method. This is being tracked by Google and will probably be fixed soon, if not by the time you read this. But if you're seeing that warning, just ignore it; it still compiles fine. This is an example of the bleeding edge on which Dart stands; the print warning was not happening when I started writing this tutorial, it's only happened with the most recent build of the Editor (build 5104).

Step 14: DOM Manipulation

We're going to create the needed HTML elements programmatically, and place them within our target <div>. Dart provides a very clean API for this kind of task.

First, let's create a few more properties to hold some of the elements. Add these right below the first property you added:

class DartMarquee {

Element _target;

DivElement _mainImage;

DivElement _thumbContainer;

DartMarquee(this._target) {

Notice how we're using underscores as a prefix? Not only this a common convention when naming private properties, it's actually idiomatic Dart. An underscore prefix makes the property (or method, or class even) private. Otherwise, it's public.

Also notice how we've typed them as DivElement? Another nice feature of Dart (as least for the web) is that it provides classes for the individual HTML elements, unlike the more generic approach usually taken in JavaScript. The upshot is that individual element types have the appropriate properties so it's easy to manipulate them with Dart. For example, ImageElements have a src property that can be safely and easily accessed directly with Dart to modify the image's source.

Now let's create those elements. In the constructor:

DartMarquee(this._target) {

_mainImage = new Element.tag('div');

_mainImage.classes = ["mainImage"];

_thumbContainer = new Element.tag('div');

_thumbContainer.classes = ["thumbContainer"];

target.nodes.add(_mainImage);

target.nodes.add(_thumbContainer);

}

There's a lot going on here; let's break it down.

First we create a new DivElement. But notice that we don't write new DivElement as you might expect (and believe me, I expected that, and continued to expect that for quite a while before I discovered the proper technique). Even though DivElement is a class, it doesn't have a constructor that you can access. Instead, you use a named constructor on the Element class to create an element of a specific type.

Named constructors are just different constructors (kind of like method overloading, but it's not really that) that can provide a different interface to the construction. In this case, we can specify by string the type of element. You can also write new Element.html('<div>...</div>'); to write out the HTML in string format. Two rather different approaches, so we have two constructors.

Once we have our _mainImage DivElement, we set its class. Element provides a classes property which lets us access the various classes that may applied. In this case, it's a brand new element, so that property is empty. We set it to a single class name, "mainImage".

You might expect classes to be an Array (or List, in Dart parlance), but it's actually a Set. A Set is similar to an Array in that it's a collection of independent values, but the key difference is that the collection is unordered; there is no guarantee that the order of the contained values will be anything in particular, or even the same each time. This has a slight ramification in how we work with the classes property, but for now it's a simple assignment to what looks like an Array containing a single String.

The next two lines are repeated almost verbatim, except that we're assigning the _thumbContainer property, and assigning a different class.

The final two lines add these new Elements to the DOM, specifically, to the target div. As you can see, there is a nodes property on the Element, which as you'd expect is a List of child elements. Being a List (or Array), we can simply add (similar to JavaScript's push) an Element into it. And at this point, the elements are in the DOM.

Go ahead and run the project again; because we've added classes to the new <div>s, and we have our CSS file ready to go, you should see a slight change to the page:

Step 15: Loading JSON

We need some content, not just grey boxes at which to look. We'll drive our little marquee with a JSON file, so let's look at how we make an HTTP request in Dart.

First, let's create the JSON file. It'll be pretty simple, and shouldn't need any explaining in and of itself. Create a new file in your Dart project (File > New File...) and name it marquee.json. Add the following content:

{

"images":[

"scottwills_machinery3.jpg",

"scottwills_machinery4.jpg",

"scottwills_machinery5.jpg",

"scottwills_machinery6.jpg",

"scottwills_machinery7.jpg",

"scottwills_machinery8.jpg"

]

}

Save, and turn back to DartMarquee.dart. We'll add the code to load this file in the constructor, after we've created our extra Elements.

XMLHttpRequest request = new XMLHttpRequest();

String url = 'marquee.json';

request.open("GET", url, true);

request.on.load.add(onJSONLoad);

request.send();

And that's how you do that.

Oh, all right, a little explanation. First, we create an XMLHttpRequest object. That will handle the loading of the data (and would also handle the sending of data if we were doing that sort of thing). The next line is a bit superfluous, but I wanted to show another variable being created. Notice that String types can be created with the quote literal, just like in JavaScript (and just about every other language). In Dart, there is no difference between single- and double-quotes, unlike PHP or Ruby.

Next we start working with the XMLHttpRequest object. First we open the connection, passing in the method ("GET"), the url we just created, and finally that we're interested in an asynchronous request (true). That means that we need to add an event listener to know when the load completes. That brings us to the most interesting line:

request.on.load.add(onJSONLoad);

This is Dart's event model. Objects that dispatch events have an on property which acts as "event central", where you can go to plan your next party. There will also be properties on the on object that correspond to the various events dispatched by the object in question; in this case, load is one of the events. Each of these event properties is actually a collection of listeners, to which we can add a new listener (onJSONLoad in this case; this hasn't been written yet in case you were wondering).

This syntax took a little getting used to, but now I really like it. It's safer and cleaner than request.addEventListener('load', onJSONLoad), wouldn't you agree?

The last line of our previous code block simply sets the request in motion; send it off to get our data.

For this to work, we need an onJSONLoad function. Let's start doing that next.

Step 16: Methods and Event Listeners

Now we get to write a new method. This method also happens to be an event listener (for the XMLHttpRequest we set up in the last step), but regardless the syntax is the same. Find a spot in the DartMarquee class that's after the close of the constructor but before the close of the class - it should be between two closing braces. Add the following:

void onJSONLoad(Event e) {

print("onJSONLoad");

}

The syntax should be fairly obvious. It follows the property/variable syntax, in that we've replaced JavaScript's function keyword with a datatype. The datatype is the type of the value returned by the function. In this case, void is actually the lack of type, as the function doesn't return anything. And similar to properties, you can optionally leave the method untyped and use the function keyword instead of a type.

Now we can try out the application. Run it again, and check the console. You should get the message that our function has run, meaning the JSON file has loaded.

Step 17: Properly Bound "this"

Let's pause in the action for a moment to talk theory. Don't worry, you'll learn something important along the way.

In the code that we just wrote to add an event listener, our event listener is properly bound to the scope of the object it belongs to. In JavaScript, this be bound to the object that dispatched the event. That is, if you write this in JavaScript:

myElement.addEventListener('click', onClick);

function onClick() { console.log(this); }

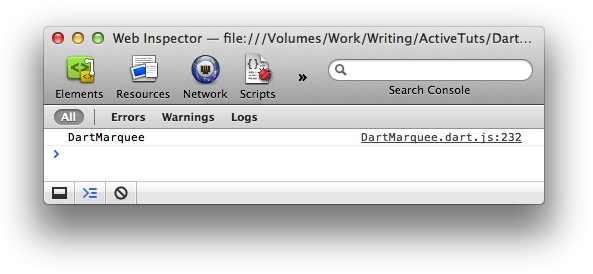

Then this refers to myElement, the object doing the event dispatching. In Dart, however, this will refer to the object to which the listener belongs. Try it out; change the print to this:

void onJSONLoad(Event e) {

print(this);

}

And run it again. You should see this:

!['this' is '[object Object]'](/uploads/posts/8033/assets/legacy/tuts/452_dartMarquee/images/14.png)

OK, that doesn't exactly prove things very well. [object Object] could be anything. Let's take a quick look at a useful trick for making your classes describe themselves.

Add a method to DartMarquee called toString. This method should return a String and take no arguments.

String toString() {

return "DartMarquee";

}

Run it one more time and now you end up with this:

This should illustrate that "this" refers to the DartMarquee object. JavaScript does not behave this way without workarounds. This means that you don't have to worry about binding functions to their scope when adding event listeners, such as with jQuery's bind method and other similar solutions.

Step 18: Generics

Let's move on and parse our JSON now that the JSON file is loaded. We're going to parse it and stuff those URLs into a property, so first let's trot back to the top of the class and add a _urls property:

Element _target; DivElement _mainImage; DivElement _thumbContainer; List<String> _urls;

This syntax will look odd if you're not coming from Java. The variable name is _urls, and the datatype is List<String>. We could just write List _urls, and that would work, but we can also take advantage of something that Dart provides. Back towards the beginning, I described reified generics, and the <String> part of the datatype is the generic. That is, the elements within the List are typed as Strings. The point of this step is pretty much to introduce this syntax. We'll see it again soon.

If you've programmed ActionScript 3, you'll find the syntax similar to Vectors, and in fact Dart Lists and AS3 Vectors are essentially the same thing.

Step 19: Parsing JSON

Now let's get to parsing. Remove the print statement from onJSONLoad and add this:

void onJSONLoad(Event e) {

XMLHttpRequest request = e.target;

Map<String, Object> result = JSON.parse(request.responseText);

print("JSON: " + result);

int i = 0;

_urls = result['images'];

_urls.forEach((url) {

print("url $i: $url");

i++;

});

}

This code really isn't so bad. Here's how it breaks down.

Line 2: This is just casting the source of the event (found in e.target) to an XMLHttpRequest so we can more safely work with properties on it.

Line 3: This one gets a little gnarly. Skip to the second half of the line. We're getting responseText out of the XMLHttpRequest object, which gives us the raw text found in our file. And we pass that into the parse method of the JSON class. That's all there is to parsing JSON; it's essentially built-in! Now, to make sure we can work with the data, we need to store it in a variable. This variable is result. Because I'm advocating strong typing, it also has a type. This type is Map<String, Object>, which might be a little frightening.

A Map is basically what we call an Object in JavaScript; it's a collection, and stores its values by a String key.

Because Map is a collection, it can be generified (see last step), but because there are technically two things we can specify (the key and the value), we supply two types. Somewhat oddly, you can't use anything other than String for the key type, so I'm not sure why it needs specified. It may be possible that Dart eventually allows the use of any type as the key. But for now, it's a String key. Because our JSON data is an Object at it's outermost, we specify Object as the value type. We have a little flexibility, depending on the JSON structure.

Line 4: Now that we have our JSON parsed, let's just print it out to verify the result.

Line 5: Initialize a counter. Note that Dart supports an int type.

Line 6: Get the images property out of the main JSON object, which should be an Array/List, and store that in our _urls property that we set up in the last step.

Line 7: Loop over that List, using forEach and an anonymous function. Note the syntax for anonymous functions: (url) {...}. If there is no return type, we can leave it off completely and just start with the parameter list. It feels a little odd at first, but ultimately leads to less code written, which is kind of nice.

Line 8: Now we can print out the URL along with its index. Here we can see that Dart has String interpolation, which lets you expand variables within a String, and avoid breaking out of a String in order to include the value of a variable. The use of the dollar sign indicates that what follows is actually a variable, and Dart should interpolate it. Again, this is less code written and leads to much more readable code than String concatenation.

Line 9: Hopefully this line of code doesn't need explanation.

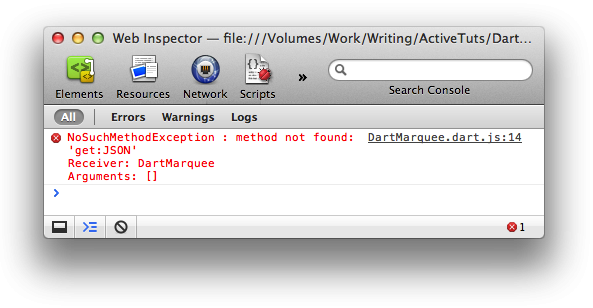

Run the application, and…uh oh. That console doesn't look pretty.

Read on for the fix.

Step 20: Importing More Libraries

The fix is, thankfully, rather simple. Dart is structured into libraries, and it turns out that JSON capability isn't part of the HTML library. We simply need to add the following line at the very top of the file:

#import('dart:json');

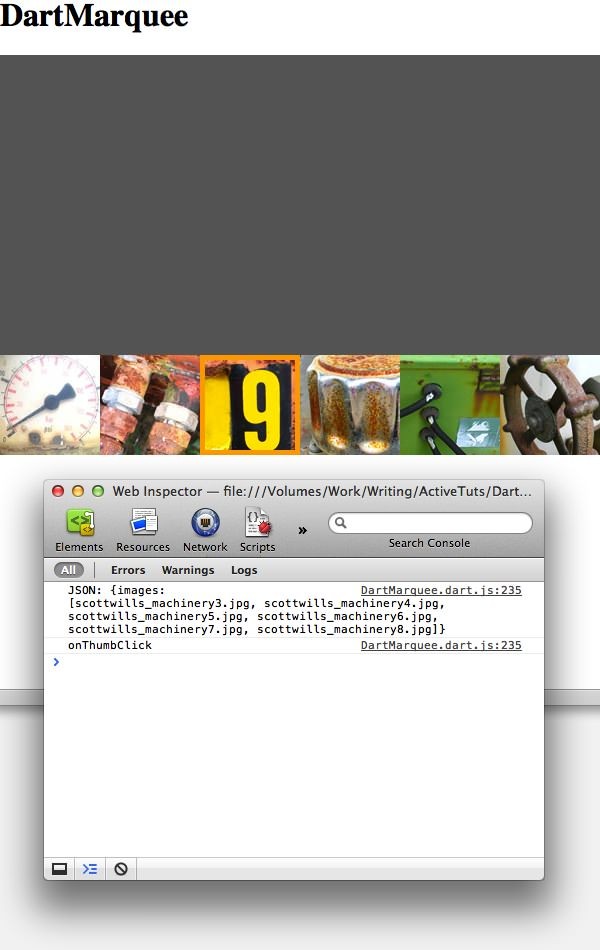

Run the project again, and you should get a console full of output:

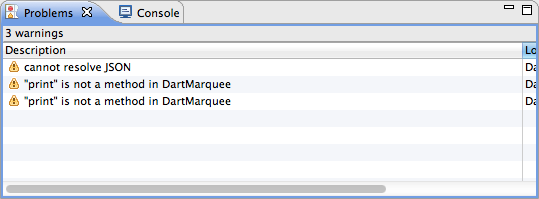

What I find odd is that this seems like something the JavaScript compiler catches, but it's only a warning. The compiler recognizes that you're using a class called JSON but doesn't know where to find that class…that seems like an important thing to catch. The lesson here, aside from where the JSON library is, is to check the Problems panel in Dart Editor. It got kind of buried amidst the false print warnings, but it was there:

Also, when you run the project, the Console panel takes over in that space, so you may have missed the warnings altogether. Just something to be on the look out for. This kind of thing will probably improve with time.

Step 21: Writing External Classes

As we continue to explore Dart's capabilities, we're going to write a new class to handle a single thumbnail image. We'll ultimately instantiate a number of these, one for each thumbnail.

While it's possible to insert a second class definition into the same file, let's see what happens when we decide to write an external class. In Dart Editor, create a new file for our project and name it MarqueeButton.dart. You'll be presented with the following template:

class MarqueeButton {

}

Again, there is no requirement that we name the class after the file, or vice versa, but it does make sense, so we'll leave well enough alone and just start filling in the details.

For now, let's just get this functional by providing a simple constructor that prints a message so we can see it working. Add a constructor to the class:

class MarqueeButton {

MarqueeButton(index, image) {

print("$index: $image");

}

}

Nothing we haven't been over already; this is a simple constructor that uses String interpolation.

But to use it, we need to make sure the DartMarquee class is aware of the MarqueeButton class. At the top of DartMarqee, where there are two #import statement, add a third line to include our new class:

#import('dart:html');

#import('dart:json');

#source('MarqueeButton.dart');

You were expecting another #import, weren't you? #source is a bit simpler than #import. #import is for libraries, which need to be declared as such and can link to other files. #source simply includes the targeted file. One thing to note is the #sourced files cannot, themselves, link to other files. Even #importing the built-in libraries will cause a compiler error. As such, this is a simple way to collect a few files into another script, but for more complex structures you may want to consider creating a library.

Now that we're linking to our new class, let's use it. Down in onJSONLoad, we'll replace the existing print with some instantiation:

void onJSONLoad(Event e) {

XMLHttpRequest request = e.target;

Map<String, Object> result = JSON.parse(request.responseText);

print("JSON: " + result);

int i = 0;

_urls = result['images'];

_urls.forEach((url) {

MarqueeButton btn = new MarqueeButton(i, "images/thumbs/" + url);

i++;

});

}

If you run the project again, you'll get more or less the same thing, only now it's logging from within the MarqueeButton class.

Step 22: Fill In the "MarqueeButton" Class

At this point, we can fill in most of the MarqueeButton class without running into much that's new. I'll present almost the full body of the class here, and discuss it briefly below.

class MarqueeButton {

DivElement _target;

String _image;

int _index;

Function _onClick;

MarqueeButton(this._index, this._image) {

_target = new Element.tag('div');

_target.classes = ["button"];

DivElement border = new Element.tag('div');

border.classes = ["border"];

_target.nodes.add(border);

_target.style.backgroundImage = 'url("'+_image+'")';

_target.on.click.add(onClick);

}

void onClick(Event e) {

_target.classes.add('selected');

_onClick(this);

}

}

We start the class off with a handful of properties, all private and typed. It may be interesting to note the Function type. We'll get to this in a moment, but this illustrates that functions are fully-fledged objects in Dart, and can be passed around by reference rather easily.

The constructor is mostly about building up the HTML elements for the button. We start from scratch; the only things passed in to the constructor are the index of the button and the image URL. We've seen this before, creating and adding new elements. Line 15, however, present something new, although I'd imagine you can figure out what it does. Elements have a style property which lets you set CSS styles rather easily. The properties available to the style object follow the CSS style names, only removing the hyphen and turning the name camel-case. Note that the value might be a String or in the case of numeric values, it can just be a number.

The last line of the constructor adds a click event listener to the button, following the convention we saw with the XMLHttpRequest events.

Then we have our onClick method, the listener for that click event. For style purposes we'll add the .selected class to the element, then we call the _onClick function. This, you'll recall, is the property we declared earlier. This is a poor man's event dispatching, and what happens is that DartMarquee will set this property to a function of its own, so that MarqueeButton can call it. We'll get to the setting in a moment, and we haven't written the relevant DartMarquee code. But because functions are first-class citizens of the Dart world, it's easy to pass that function around, and execute it somewhat arbitrarily.

Step 23: Setters and Getters

We'll finish off the class with some getters and a setter. For the uninitiated, setters and getters are special functions that simply return a value (getters), or receive a value (setters). They're common enough, and most object-oriented languages provide some method for creating implicit setters and getters, which are functions that are called as if they were properties.

Dart has this, as well, and throws some syntactic sugar on top of it, to boot. Add this to the end of the class (before the closing curly brace, but after the onClick method):

DivElement get target() => _target;

int get index() => _index;

Function get click() => _onClick;

void set click(Function fn) {

_onClick = fn;

}

You can see the sugar in the three getters. Each one follows this pattern:

Type get name() => expression;

The type is nothing new; it's the return type of the function. The get keyword signifies that this is an implicit getter function. name() is just the name of the method. Next is the => operator, which basically says "return the value that is expressed on my right." In the case of _target, we're simply accessing the value stored in the _target property and returning that. In other words, a basic getter method, written with a little less code than normal.

The expression can actually get a little more complicated than that, such as a boolean check or some simple one-liner math. If it's going to require more than one line of code, it needs to be written as a regular getter, which is just like a regular method except for the get keyword:

DivElement get target() {

return _target;

}

We're done with the MarqueeButton class now, so we'll turn back to the DartMarquee class and start using it.

Step 24: Displaying Thumbnails

To display the buttons, we need to go back to the DartMarquee class and revisit the onJSONLoad method. Specifically, we need to add to that loop.

_urls.forEach((url) {

MarqueeButton btn = new MarqueeButton(i, "images/thumbs/" + url);

_thumbContainer.nodes.add(btn.target);

btn.click = onThumbClick;

i++;

});

Another nodes.add(), this time on the _thumbContainer div and adding the target of the MarqueeButton object.

Then we set the click property to a method we have yet to write, but will do so now:

void onThumbClick(MarqueeButton btn) {

print("onThumbClick");

}

We'll work on this next, but for now we should be able to run the application, see the thumbnails, and click on them to see the log message.

We're almost there. We'll work on getting that click to mean something in the next two steps.

Step 25: Handling the Click

The logic involved in displaying a larger image isn't terribly complex, and at this point we've had a pretty extensive tour of the Dart language. I'll start listing the method here, and then discuss what's going on.

First we need two properties declared. At the top of the class, with the other properties, add these lines:

MarqueeButton _currentButton; ImageElement _currentImage;

Then update onThumbClick:

void onThumbClick(MarqueeButton btn) {

if (_currentButton != null) {

_currentButton.target.classes.remove('selected');

}

_currentButton = btn;

ImageElement image = new Element.tag('img');

image.width = 600;

image.height = 300;

image.src = "images/" + _urls[btn.index];

_mainImage.nodes.add(image);

}

The first thing to notice is that we're checking for the existence of a value in _currentButton. If it does, then we remove the .selected class. Then we set the _currentButton property to the button that was clicked, for next time.

It's worth nothing that Dart handles Booleans a little differently than you may be used to. Seth Ladd has a write-up on Booleans in Dart, in which we explains:

Dart has a true boolean type named bool, with only two values: true and false (and, I suppose, null). Due to Dart's boolean conversion rules, all values except true are converted to false. Dart's boolean expressions return the actual boolean result, not the last encountered value.

Therefore, when checking for the existence of a value within a variable, it's wise to write if (variable != null) as opposed to the shorthand if (variable), as that could actually report false even through the variable has a valid value stored in it.

Next we create an image element, set its size, the src, and then add it as a child.

You should be able to try this out now. We won't get a nice fade between the images, but you should now be able to use the marquee to switch images.

Step 26: Working with the Transition

Let's work on that fade. Add the highlighted code below to the onThumbClick method. Note that Line 11 is a change from how it was before (it uses insertAdjacentElement), and the lines after that are new.

void onThumbClick(MarqueeButton e) {

if (_currentButton != null) {

_currentButton.target.classes.remove('selected');

print(_currentButton.target.classes);

}

_currentButton = e;

ImageElement image = new Element.tag('img');

image.width = 600;

image.height = 300;

image.src = "images/" + _urls[e.index];

_mainImage.insertAdjacentElement('afterBegin', image);

if (_currentImage != null) _currentImage.classes.add('fade_away');

_currentImage = image;

image.on.transitionEnd.add((evt) {

ImageElement img = evt.target;

img.remove();

});

}

The change to line 53 introduces another way to add children elements. Element.nodes.add() is fine for appending at the end, but if we want to insert in a specific place, in this case at the beginning, then nodes doesn't give us enough options. insertAdjacentElement does provide options, although its interface isn't as clean as it could be. In fact, it's lifted from the Windows Internet Explorer API. I try not to get too opinionated in a tutorial, but this is an odd decision.

Regardless, it's the API we have if we want to do more than append to the child elements. We want to add our new image to the beginning, so we pass in "afterBegin" to insertAdjacentElement, which does exactly that. This method is documented at MSDN if you'd like a description of the various valid arguments to that parameter.

The rest of the code involves itself with the CSS3 transition; by adding a .fade_away class to the old image (after checking to be sure it's not null) we set it's opacity to 0, invoking the transition. Then _currentImage is set to the new image, to get set for the next transition.

Finally, another event listener is added to the current image so that when the transition happens, and is finished, we can run a bit of code. All we do is get the event target and cast it as an ImageElement (not strictly necessary, but it's something that I find useful to do in general). Then by calling remove() on the ImageElement, we remove it from the DOM. In other words, once it fade away completely, we can remove it altogether to keep our DOM tidy.

Note also that we're using another anonymous function as the event listener in this case. Either way would work, but since this is practically a one-line function, making it anonymous is rather convenient.

Run the application, click on one thumb to load an image, then another thumb and watch it in silent awe.

Step 27: The Final Touch

Our Dart application is rather functional now, but you've probably noticed that it has one minor flaw: there is not image loaded up right away. This is a simple fix.

In Marquee.dart, find the onJSONLoad method and add the highlighted line of code toward the bottom:

void onJSONLoad(Event e) {

XMLHttpRequest request = e.target;

Map<String, Object> result = JSON.parse(request.responseText);

print("JSON: " + result);

int i = 0;

_urls = result['images'];

_urls.forEach((url) {

MarqueeButton btn = new MarqueeButton(i, "images/thumbs/" + url);

_thumbContainer.nodes.add(btn.target);

btn.click = onThumbClick;

if (i == 0) btn.onClick(null);

i++;

});

}

In effect, if we're on the first iteration, take that MarqueeButton and call its onClick method. You'll remember that as the event listener for the click event within the MarqueeButton. We'll just call it directly, to sort of simulate a click on the first button, so as to trigger the setting of the styles and putting content in the right place. Since the method expects an event parameter, but isn't really used, we can supply null to the method call to satisfy the compiler.

Run it once more, and you should now have the first image selected and ready in the main area.

Step 28: Where To Go From Here

We've just scratched the surface of Dart, but the cool thing is that if you know JavaScript, you already know Dart in one sense. You're already familiar with what you can do with an HTML page, and generally how to do it. Dart for the web doesn't really add any capabilities or fancy frameworks, it's just another language in the same problem domain. If you want to learn more, you can do worse than to simply write applications in Dart. Maybe dig out a smallish/simple bit of JavaScript you've done and port it over to Dart.

If you like scouring the web for more resources, Google is certainly your friend, although the name "Dart" can lead to many unrelated hits that are about the game of darts, rather than the language. Many times I've had to specify "dart language" in my searches or get a little more specific than just "dart events". There is quite a bit of information floating around.

First, the official Dart website is at dartlang.org. You'll find a small tutorial there that goes into some of the unique language features, along with the nifty Dartboard widget that lets your write and execute dart code in the browser you can even use the widget on your own site).

If you think you know what you need to do, just don't know the right method name or class, the API documentation is good place to start, at api.dartlang.org. Sometimes the docs are a little bare or even wrong, but you should probably begin any quest for an answer here.

I've already mentioned the mailing list, located at groups.google.com/a/dartlang.org/group/misc/topics. It's very active and I had a few questions answered in a matter of minutes there. The Google engineers are very involved on the list, as well.

The Dart site also has a pretty nice JavaScript-to-Dart comparison chart, located at synonym.dartlang.org, which takes common JavaScript code snippets and shows the equivalent Dart code right beside it.

Moving away from Google's own resources, there are a few Dart-centric blogs that kept coming up in searches. One of the most prolific is Japh(r) by Chris Strom, at japhr.blogspot.com/search/label/dartlang, who is also writing a book on Dart.

The Dartosphere (dartosphere.org aggregates several different blogs about Dart, and can be a gold mine of information.

Seth Ladd works at Google, and his blog at blog.sethladd.com has been recently devoted to Dart.

DartWatch, at dartwatch.com, is another Dart-centric blog that has plenty of content to keep you busy.

One problem, however, is that Dart is a bit of a moving target currently, and some of the older posts on blogs might be out-of-date by the time you get to them. Just keep that in mind. The mailing list is the best place to go if you can't find a solution through a web search.

One last resource: if this tutorial sparks some interest amongst Tuts+ readers, then we'll probably find a few more tutorials to write that delve deeper into the world of Dart.

Step 29: Regarding Events

In this tutorial, we learned how to attach event listeners to object, for example:

someElement.on.click.add(myClickListener); someHTTPRequest.on.load.add(myLoadListener);

You may have noticed that we did not leverage this model when we needed to have the MarqueeButton object communicate to the DartMarquee object. We went for a more lo-fi event listener, where we simply pass a Function in to the object, and then call that Function from within the object. You may ask yourself, why did we do that? Why didn't we use the on property to dispatch an event? Where does that highway lead to?

The answer is that Dart doesn't provide this event mechanism outside of its own objects. Not only that, that event system is only available to objects in the HTML libraries. This feels like an area where Google might be able to open up. It sure would be nice to have our own classes become event dispatchers by simply extending an EventDispatcher class or similar, and with a little bit of code getting that mechanism for free.

It's possible to build your own system that mimics the built-in mechanism, but for the purposes of this tutorial, I went the lo-fi route. There may be some future Dart tutorials that go deeper.

Conclusion

Is Dart the future? Some say yes, some say no. I say, "I don't know". I'm certainly intrigued by the possibilities, and as long as it compiles to usable JavaScript today, then maybe it doesn't matter if Dart isn't interpreted natively by all of the browsers.

For now, I would say that if CoffeeScript is something that's been catching on, then the Dart-to-JavaScript technique certainly has the same opportunity. Unlike CoffeeScript, though, you end up with some overhead JavaScript, which may not be appropriate for a vast majority of JavaScript-enabled web pages today. For instance, our DartMarquee project compiles into a JavaScript that's over 100 KB. That's a bit much for such a simple marquee. One should be able to write that in regular JavaScript, aided by jQuery or a similar library, for well under that weight limit. And the niceties provided by Dart, with classes, typing, and imports, aren't enough for this small application to really justify the size.

But for larger applications, like Google Docs, 280 Slides, or Mockingbird, then you can very easily justify the overhead. You'll have hundreds of KB of JavaScript anyway, so a little extra for the compilation process in exchange for a more structured set of classes will definitely appeal to some programmers.

That's all for this introduction to Dart. Thanks for reading. I hope it was enlightening for you!

Comments