In the previous article, we explored the basics of functions in Swift. Functions, however, have a lot more to offer. In this article, we continue our exploration of functions and look into function parameters, nesting, and types.

1. Local and External Parameter Names

Parameter Names

Let us revisit one of the examples from the previous article. The printMessage(message:) function defines one parameter, message.

func printMessage(message: String) {

print(message)

}

We assign a name, message, to the parameter and use this name when we call the function.

printMessage(message: "Hello, world!")

But notice that we also use the same name to reference the value of the parameter in the body of the function.

func printMessage(message: String) {

print(message)

}

In Swift, a parameter always has a local parameter name, and it optionally has an external parameter name. In the example, the local and external parameter names are identical.

API Guidelines

As of Swift 3, the Swift team has defined a clear set of API guidelines. I won't go into those guidelines in this tutorial, but I want to point out that the definition of the printMessage(message:) function deviates from those guidelines. The name of the function contains the word message, and the parameter is also named message. In other words, we are repeating ourselves.

It would be more elegant if we could invoke the printMessage(message:) function without the message keyword. This is what I have in mind.

printMessage("Hello, world!")

This is possible, and it is more in line with the Swift API guidelines. But what is different? The difference is easy to spot if we take a look at the updated function definition. The updated example also reveals more about the anatomy of functions in Swift.

func printMessage(_ message: String) {

print(message)

}

In a function definition, each parameter is defined by an external parameter name, a local parameter name, a colon, and the type of the parameter. If the local and external parameter names are identical, we only write the parameter name once. That is why the first example defines one parameter name, message.

If we don't want to assign an external parameter name to a parameter, we use the _, an underscore. This informs the compiler that the parameter doesn't have an external parameter name, and that means we can omit the parameter name when the function is invoked.

External Parameter Names

Objective-C is known for its long method names. While this may look clunky and inelegant to outsiders, it makes methods easy to understand and, if chosen well, very descriptive. The Swift team understood this advantage and introduced external parameter names from day one.

When a function accepts several parameters, it isn't always obvious which argument corresponds to which parameter. Take a look at the following example to better understand the problem. Notice that the parameters don't have an external parameter name.

func power(_ a: Int, _ b: Int) -> Int {

var result = a

for _ in 1..<b {

result = result * a

}

return result

}

The power(_:_:) function raises the value of a by the exponent b. Both parameters are of type Int. While most people will intuitively pass the base value as the first argument and the exponent as the second argument, this isn't clear from the function's type, name, or signature. As we saw in the previous article, invoking the function is straightforward.

power(2, 3)

To avoid confusion, we can give the parameters of a function external names. We can then use these external names when the function is called to unambiguously indicate which argument corresponds to which parameter. Take a look at the updated example below.

func power(base a: Int, exponent b: Int) -> Int {

var result = a

for _ in 1..<b {

result = result * a

}

return result

}

Note that the function's body hasn't changed since the local names haven't changed. However, when we invoke the updated function, the difference is clear and the result is less confusing.

power(base: 2, exponent: 3)

While the types of both functions are identical, (Int, Int) -> Int, the functions are different. In other words, the second function isn't a redeclaration of the first function. The syntax to invoke the second function may remind you of Objective-C. Not only are the arguments clearly described, but the combination of function and parameter names also describe the purpose of the function.

In some cases, you want to use the same name for the local and the external parameter name. This is possible, and there's no need to type the parameter name twice. In the following example, we use base and exponent as the local and external parameter names.

func power(base: Int, exponent: Int) -> Int {

var result = base

for _ in 1..<exponent {

result = result * base

}

return result

}

By defining one name for each parameter, the parameter name serves as the local and external name of the parameter. This also means that we need to update the body of the function.

It's important to note that by providing an external name for a parameter, you are required to use that name when invoking the function. This brings us to default values.

Default Values

We covered default parameter values in the previous article. This is the function we defined in that article.

func printDate(date: Date, format: String = "YY/MM/dd") -> String {

let dateFormatter = DateFormatter()

dateFormatter.dateFormat = format

return dateFormatter.string(from: date)

}

What happens if we don't define an external parameter name for the second parameter, which has a default value?

func printDate(date: Date, _ format: String = "YY/MM/dd") -> String {

let dateFormatter = DateFormatter()

dateFormatter.dateFormat = format

return dateFormatter.string(from: date)

}

The compiler doesn't seem to care. But is this what we want? It is best to define an external parameter name to optional parameters (parameters with a default value) to avoid confusion and ambiguity.

Notice that we are repeating ourselves again in the previous example. There is no need to define an external parameter name for the date parameter. The next example shows what the printDate(_:format:) function would look like if we followed the Swift API guidelines.

func printDate(_ date: Date, format: String = "YY/MM/dd") -> String {

let dateFormatter = DateFormatter()

dateFormatter.dateFormat = format

return dateFormatter.string(from: date)

}

We can now invoke the formatDate(_:format:) function without using the date label for the first parameter and with an optional date format.

printDate(Date()) printDate(Date(), format: "dd/MM/YY")

2. Parameters and Mutability

Let us revisit the first example of this tutorial, the printMessage(_:) function. What happens if we change the value of the message parameter inside the function's body?

func printMessage(_ message: String) {

message = "Print: \(message)"

print(message)

}

It doesn't take long for the compiler to start complaining.

The parameters of a function are constants. In other words, while we can access the values of function parameters, we cannot change their value. To work around this limitation, we declare a variable in the function's body and use that variable instead.

func printMessage(_ message: String) {

var message = message

message = "Print: \(message)"

print(message)

}

3. Variadic Parameters

While the term may sound odd at first, variadic parameters are common in programming. A variadic parameter is a parameter that accepts zero or more values. The values need to be of the same type. Using variadic parameters in Swift is trivial, as the following example illustrates.

func sum(_ args: Int...) -> Int {

var result = 0

for a in args {

result += a

}

return result

}

sum(1, 2, 3, 4)

The syntax is easy to understand. To mark a parameter as variadic, you append three dots to the parameter's type. In the function body, the variadic parameter is accessible as an array. In the above example, args is an array of Int values.

Because Swift needs to know which arguments correspond to which parameters, a variadic parameter is required to be the last parameter. It also implies that a function can have at most one variadic parameter.

The above also applies if a function has parameters with default values. The variadic parameter should always be the last parameter.

4. In-Out Parameters

Earlier in this tutorial, you learned that the parameters of a function are constants. If you want to pass a value into a function, modify it in the function, and pass it back out of the function, in-out parameters are what you need.

The following example shows an example of how in-out parameters work in Swift and what the syntax looks like.

func prefixString(_ string: inout String, with prefix: String) {

string = prefix + string

}

We define the first parameter as an in-out parameter by adding the inout keyword. The second parameter is a regular parameter with an external name of withString and a local name of prefix. How do we invoke this function?

var input = "world!" prefixString(&input, with: "Hello, ")

We declare a variable, input, of type String and pass it to the prefixString(_:with:) function. The second parameter is a string literal. By invoking the function, the value of the input variable becomes Hello, world!. Note that the first argument is prefixed with an ampersand, &, to indicate that it is an in-out parameter.

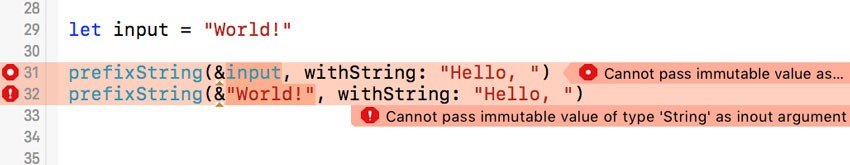

It goes without saying that constants and literals cannot be passed in as in-out parameters. The compiler throws an error when you do as illustrated in the following examples.

It's evident that in-out parameters cannot have default values or be variadic. If you forget these details, the compiler kindly reminds you with an error.

5. Nesting

In C and Objective-C, functions and methods cannot be nested. In Swift, however, nested functions are quite common. The functions we saw in this and the previous article are examples of global functions—they are defined in the global scope.

When we define a function inside a global function, we refer to that function as a nested function. A nested function has access to the values defined in its enclosing function. Take a look at the following example to better understand this.

func printMessage(_ message: String) {

let a = "hello world"

func printHelloWorld() {

print(a)

}

}

While the functions in this example aren't terribly useful, they illustrate the idea of nested functions and capturing values. The printHelloWorld() function is only accessible from within the printMessage(_:) function.

As illustrated in the example, the printHelloWorld() function has access to the constant a. The value is captured by the nested function and is therefore accessible from within that function. Swift takes care of capturing values, including managing the memory of those values.

6. Function Types

Functions as Parameters

In the previous article, we briefly touched upon function types. A function has a particular type, composed of the function's parameter types and its return type. The printMessage(_:) function, for example, is of type (String) -> (). Remember that () symbolizes Void, which is equivalent to an empty tuple.

Because every function has a type, it's possible to define a function that accepts another function as a parameter. The following example shows how this works.

func printMessage(_ message: String) {

print(message)

}

func printMessage(_ message: String, with function: (String) -> ()) {

function(message)

}

let myMessage = "Hello, world!"

printMessage(myMessage, with: printMessage)

The printMessage(_:with:) function accepts a string as its first parameter and a function of type (String) -> () as its second parameter. In the function's body, the function that we pass in is invoked with the message argument.

The example also illustrates how we can invoke the printMessage(_:with:) function. The myMessage constant is passed in as the first argument and the printMessage(_:) function as the second argument. How cool is that?

Functions as Return Types

It is also possible to return a function from a function. The next example is a bit contrived, but it illustrates what the syntax looks like.

func compute(_ addition: Bool) -> (Int, Int) -> Int {

func add(_ a: Int, _ b: Int) -> Int {

return a + b

}

func subtract(_ a: Int, _ b: Int) -> Int {

return a - b

}

if addition {

return add

} else {

return subtract

}

}

let computeFunction = compute(true)

let result = computeFunction(1, 2)

print(result)

The compute(_:) function accepts a boolean and returns a function of type (Int, Int) -> Int. The compute(_:) function contains two nested functions that are also of type (Int, Int) -> Int, add(_:_:) and subtract(_:_:).

The compute(_:) function returns a reference to either the add(_:_:) or the subtract(_:_:) function, based on the value of the addition parameter.

The example also shows how to use the compute(_:) function. We store a reference to the function that is returned by the compute(_:) function in the computeFunction constant. We then invoke the function stored in computeFunction, passing in 1 and 2, store the result in the result constant, and print the value of result in the standard output. The example may look complex, but it is actually easy to understand if you know what is going on.

Conclusion

You should now have a good understanding of how functions work in Swift and what you can do with them. Functions are fundamental to the Swift language, and you will use them extensively when working with Swift.

In the next article, we dive head first into closures—a powerful construct reminiscent of blocks in C and Objective-C, closures in JavaScript, and lambdas in Ruby.

If you want to learn how to use Swift 3 to code real-world apps, check out our course Create iOS Apps With Swift 3. Whether you're new to iOS app development or are looking to make the switch from Objective-C, this course will get you started with Swift for app development.

SwiftCreate iOS Apps With Swift 3

SwiftCreate iOS Apps With Swift 3 SwiftCode a Side-Scrolling Game With Swift 3 and SpriteKit

SwiftCode a Side-Scrolling Game With Swift 3 and SpriteKit iOSWhat's New in iOS 10

iOSWhat's New in iOS 10

Comments