In a world dominated by social media, it's hard to not come across a client application which you have used to access restricted resources on some other server, for example, you might have used a web-based application (like NY Times) to share an interesting news article on your Facebook wall or tweet about it. Or, you might have used Quora's iPhone app that accesses your Facebook or Google+ profile and customizes the results based on your profile data, like suggesting to add/invite other users to Quora, based on your friends list. The question is, how do these applications gain access to your Facebook, Twitter or Google+ accounts and how are they able to access your confidential data? Before they can do so, they must present some form of authentication credentials and authorization grants to the resource server.

Introduction to OAuth 2.0

OAuth is often described as a valet key for the web.

Now, it would be really uncool to share your Facebook or Google credentials with any third-party client application that only needs to know about your Friends, as it not only gives the app limitless and undesirable access to your account, but it also has the inherent weakness associated with passwords. This is where OAuth comes into play, as it outlines an access-delegation/authorization framework that can be employed without the need of sharing passwords. For this reason, OAuth is often described as a valet key for the web. It can be thought of as a special key that allows access to limited features and for a limited period of time without giving away full control, just as the valet key for a car allows the parking attendant to drive the car for a short distance, blocking access to the trunk and the on-board cell phone.

However, OAuth is not a new concept, but a standardization and combined wisdom of many well established protocols. Also worth noting is that OAuth is not just limited to social-media applications, but provides a standardized way to share information securely between various kinds of applications that expose their APIs to other applications. OAuth 2.0 has a completely new prose and is not backwards compatible with its predecessor spec. Having said that, it would be good to first cover some basic OAuth2.0 vocabulary before diving into further details.

- Resource Owner : An entity capable of granting access to a protected resource. Most of the time, it's an end-user.

- Client : An application making protected resource requests on behalf of the resource owner and with its authorization. It can be a server-based, mobile (native) or a desktop application.

- Resource Server : The server hosting the protected resources, capable of accepting and responding to protected resource requests.

- Authorization Server : The server issuing access grants/tokens to the client after successfully authenticating the resource owner and obtaining authorization.

- Access Token : Access tokens are credentials presented by the client to the resource server to access protected resources. It's normally a string consisting of a specific scope, lifetime and other access attributes and it may self contain the authorization information in a verifiable manner.

- Refresh Token : Although not mandated by the spec, access tokens ideally have an expiration time which can last anywhere from a few minutes to several hours. Once an access token is expired, the client can request the authorization server to issue a new access token using the refresh token issued by the authorization server.

What's Wrong With OAuth 1.0?

OAuth 1.0's major drawback was the inherent complexity needed to implement the spec.

Nothing really! Twitter still works perfectly fine with OAuth 1.0 and just started supporting a small portion of the 2.0 spec. OAuth 1.0 was a well thought spec and it allowed exchange of secret information securely without the overhead imposed by SSL. The reason why we needed a revamp was mostly based around the complexity faced in implementing the spec. The following are some areas where OAuth 1.0 failed to impress:

- Signing Every Request : Having the client generate signatures on every API request and validating them on the server everytime a request is received, proved to be major setback for developers, as they had to parse, encode and sort the parameters before making a request. OAuth 2.0 removed this complexity by simply sending the tokens over SSL, solving the same problem at network level. No signatures are required with OAuth 2.0.

- Addressing Native Applications : With the evolution of native applications for mobile devices, the web-based flow of OAuth 1.0 seemed inefficient, mandating the use of user-agents like a Web Browser. OAuth 2.0 have accommodated more flows specifically suitable for native applications.

- Clear Separation of Roles : OAuth 2.0 provides the much needed separation of roles for the authorization server authenticating and authorizing the client, and that of the resource server handling API calls to access restricted resources.

OAuth 2.0 in Depth

Before initiating the protocol, the client must register with the authorization server by providing its client type, its redirection URL (where it wants the authorization server to redirect to after the resource owner grants or rejects the access) and any other information required by the server and in turn, is given a client identifier (client_id) and client secret (client_secret). This process is known as Client Registration. After registering, the client may adopt one of the following flows to interact with the server.

Various OAuth Flows

OAuth 2.0 brings about five new flows to the table and gives developers the flexibility to implement any one of them, depending on the type of client involved:

- User-Agent Flow : Suitable for clients typically implemented in user-agents (for example, clients running inside a web browser) using a scripting language such as JavaScript. Mostly used by native applications for mobile or desktop, leveraging the embedded or external browser as the user-agent for authorization and it uses the Implicit Grant authorization.

- Web Server Flow : This makes use of the Authorization Code grant and is a redirection-based flow which requires interaction with the end-user's user-agent. Thus, it is most suitable for clients which are a part of web-server based applications, that are typically accessed via a web browser.

- Username and Password Flow : Used only when there is a high trust between the client and the resource owner and when other flows are not viable, as it involves the transfer of the resource owner's credentials. Examples of clients can be a device operating system or a highly privileged application. This can also be used to migrate existing clients using HTTP Basic or Digest Authentication schemes to OAuth by converting the stored credentials to an access token.

- Assertion Flow : Your client can present an assertion such as SAML Assertion to the authorization server in exchange for an access token.

- Client Credentials Flow : OAuth is mainly used for delegated access, but there are cases when the client owns the resource or already has been granted the delegated access outside of a typical OAuth flow. Here you just exchange client credentials for an access token.

Discussing each flow in detail would be out of the scope of this article and I would rather recommend reading the spec for in-depth flow information. But to get a feel for what's going on, let's dig deeper into one of the most used and supported flows: The Web Server Flow.

The Web Server Flow

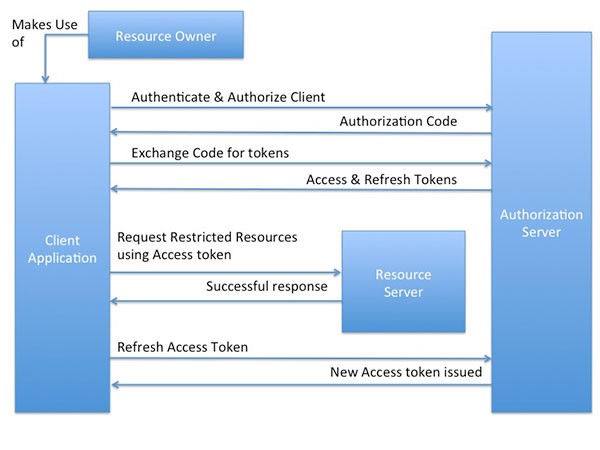

Since this is a redirection-based flow, the client must be able to interact with the resource owner's user agent (which in most cases is a web browser) and hence is typically suited for a web application. The below diagram is a bird's eye view of how the end-user (or the resource owner) uses the client application (web-server based application in this case) to authenticate and authorize with the authorization server, in order to access the resources protected by the resource server.

Authenticate & Authorize the Client

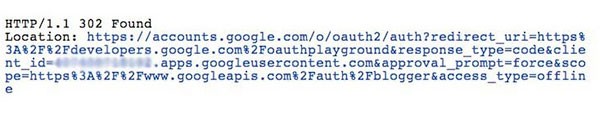

The client, on behalf of the resource owner, initiates the flow by redirecting to the authorization endpoint with a response_type parameter as code, a client identifier, which is obtained during client registration, a redirection URL, a requested scope (optional) and a local state (if any). To get a feel for how it really works, here's a screenshot of how a typical request/response would look like:

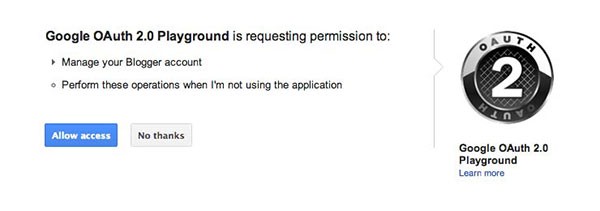

This normally presents the resource owner with a web interface, where the owner can authenticate and check what all permissions the client app can use on the owner's behalf.

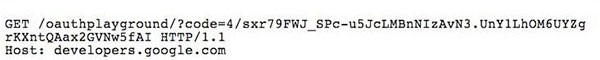

Assuming that the resource owner grants access to the client, the authorization server redirects the user-agent back to the client using the redirection URL provided earlier, along with the authorization code as shown by the response below.

Exchange Authorization Code for Tokens

The client then posts to another authorization endpoint and sends the authorization code received in the earlier step, along with the redirection URL, its client identifier and secret, obtained during client registration and a grant_type parameter must be set as authorization_code.

The server then validates the authorization code and verifies that the redirection URL is the same as it was in the earlier step. If successful, the server responds back with an access token and optionally, a refresh token.

Request Restricted Resources Using Access Tokens

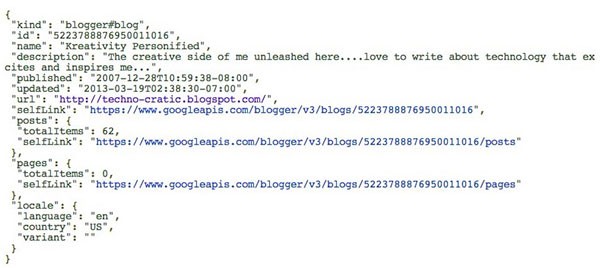

The client can now consume the APIs provided by the implementation and can query the resource server for a restricted resource by passing along the access token in the Authorization header of the request. A sample CURL request to Google's Blogger API to get a blog, given its identifier, would look like this:

$ curl https://www.googleapis.com/blogger/v3/blogs/5223788876950011016 -H 'Authorization: OAuth ya29.AHES6ZRTj1GNxAby81Es-p_YPWWNBAFRvBYVsYj2HZJfJHU'

Note that we have added the Access token as an Authorization header in the request and also escaped the token by including it in single quotes, as the token may contain special characters. Keep in mind that escaping the access token is only required when using curl. It results in sending the following request:

The resource server then verifies the passed credentials (access token) and if successful, responds back with the requested information.

These examples are courtesy of OAuth2.0 Playground and are typical to how Google implements the spec. Differences might be observed when trying the same flow with other providers (like Facebook or Salesforce) and this is where interoperability issues creep in, which we discuss a bit later.

Refreshing Access Token

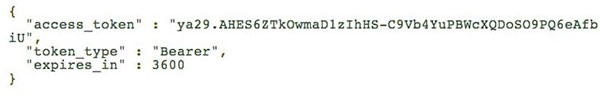

Although not mandated by the spec, but usually the access tokens are short-lived and come with an expiration time. So when an access token is expired, the client sends the refresh token to the authorization server, along with its client identifier and secret, and a grant_type parameter as refresh_token.

The authorization server then replies back with the new value for the access token.

Although a mechanism does exist to revoke the refresh token issued, but normally the refresh token lives forever and must be protected and treated like a secret value.

What's Wrong With OAuth 2.0?

The Good Stuff

Going by the adoption rate, OAuth 2.0 is definitely an improvement over its arcane predecessor. Instances of developer community faltering while implementing the signatures of 1.0 are not unknown. OAuth 2.0 also provides several new grant types, which can be used to support many use-cases like native applications, but the USP of this spec is its simplicity over the previous version.

The Bad Parts

There are a few loose ends in the specification, as it fails to properly define a few required components or leaves them up to the implementations to decide, such as:

Loose ends in the OAuth 2.0 spec are likely to produce a wide range of non-interoperable implementations.

- Interoperability: Adding too many extension points in the spec resulted in implementations that are not compatible with each other, what that means is that you cannot hope to write a generic piece of code which uses Endpoint Discovery to know about the endpoints provided by the different implementations and interact with them, rather you would have to write separate pieces of code for Facebook, Google, Salesforce and so on. Even the spec admits this failure as a disclaimer.

- Short Lived Tokens: The spec does not mandate the lifetime and scope of the issued tokens. The implementation is free to have a token live forever. Although most of the implementations provide us with short-lived access tokens and a refresh token, which can be used to get a fresh access token.

- Security: The spec just "recommends" the use of SSL/TLS while sending the tokens in plaintext over the wire. Although, every major implementation has made it a requirement to have secure authorization endpoints as well require that the client must have a secure redirection URL, otherwise it will be way too easy for an attacker to eavesdrop on the communication and decipher the tokens.

The Ugly Spat

It took IETF about 31 draft versions and the resignation of the lead author/developer Eran Hammer from the committee to finally publish the spec. Eran sparked a controversy by calling the spec "a bad protocol and a case of death by a thousand cuts". According to him, the use of bearer tokens (sending tokens over SSL without signing them or any other verification) over the user of signatures (or MAC-Tokens), used in OAuth 1.0 to sign the request, was a bad move and a result of division of interests between the web and enterprise communities.

Conclusive Remarks

The spec surely leaves many extension points out in open, resulting in implementations that introduce their own parameters, in addition to what the spec already defines, and makes sure that implementations from different providers can't interoperate with each other. But going with the popularity and adoption rate of this framework, with every big player in town (Google, Twitter, Facebook, Salesforce, Foursquare, Github etc.) implementing and tweaking it the way it suits them, OAuth is far from being a failure. In fact, any web application that plans to expose their APIs to other web applications must support some form of authentication and authorization and OAuth fits the bill here.

Comments