The whole point of maintaining "safe" copies of a software project is peace of mind: should your project suddenly break, you'll know that you have easy access to a functional version, and you'll be able to pinpoint precisely where the problem was introduced. To this end, recording commits is useless without the ability to undo changes. However, since Git has so many components, "undoing" can take on many different meanings. For example, you can:

- Undo changes in the working directory

- Undo changes in the staging area

- Undo an entire commit

To complicate things even further, there are multiple ways to undo a commit. You can either:

- Simply delete the commit from the project history.

- Leave the commit as is, using a new commit to undo the changes introduced by the first commit.

Git has a dedicated tool for each of these situations. Let's start with the working directory.

Undoing in the Working Directory

The period of time immediately after saving a safe copy of a project is one of great innovation. Empowered by the knowledge that you're free to do anything you want without damaging the code base, you can experiment to your heart's content. However, this carefree experimentation often takes a wrong turn and leads to a working directory with a heap of off-topic code. When you reach this point, you'll probably want to run the following commands:

git reset --hard HEAD git clean –f

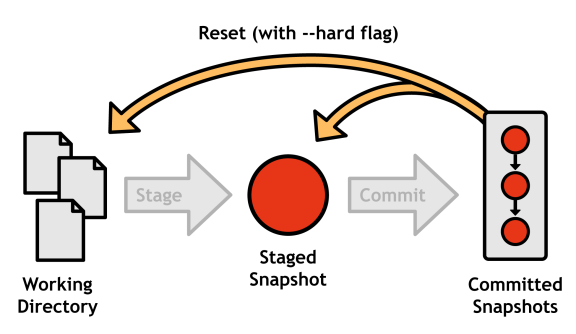

This configuration of git reset makes the working directory and the stage match the files in the most recent commit (also called HEAD), effectively obliterating all uncommitted changes in tracked files. To dispose of untracked files, you have to use the git clean command. Git is very careful about removing code, so you must also supply the -f option to force the deletion of these files.

Individual Files

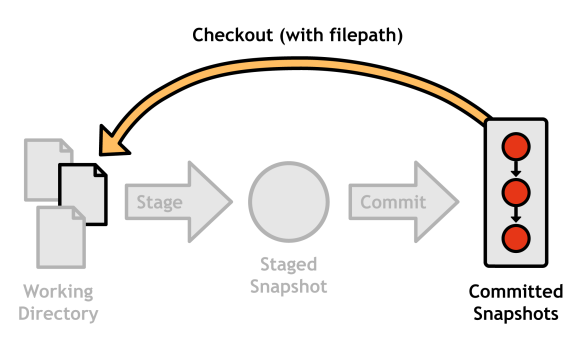

It's also possible to target individual files. The following command will make a single file in the working directory match the version in the most recent commit.

git checkout HEAD <file>

This command doesn't change the project history at all, so you can safely replace HEAD with a commit ID, branch, or tag to make the file match the version in that commit. But, do not try this with git reset, as it will change your history (explained in Undoing Commits).

git checkoutUndoing in the Staging Area

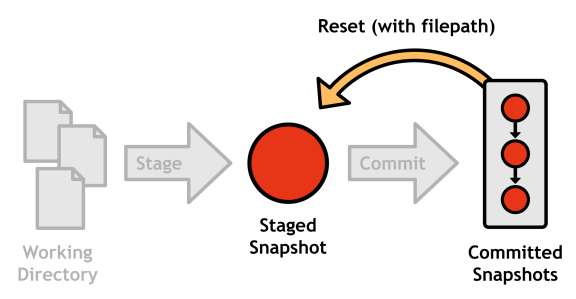

In the process of configuring your next commit, you'll occasionally add an extra file to the stage. The following invocation of git reset will unstage it:

git reset HEAD <file>

Omitting the --hard flag tells Git to leave the working directory alone (opposed to git reset --hard HEAD, which resets every file in both the working directory and the stage). The staged version of the file matches HEAD, and the working directory retains the modified version. As you might expect, this results in an unstaged modification in your git status output.

git resetUndoing Commits

There are two ways to undo a commit using Git: You can either reset it by simply removing it from the project history, or you can revert it by generating a new commit that gets rid of the changes introduced in the original. Undoing by introducing another commit may seem excessive, but rewriting history by completely removing commits can have dire consequences in multi-user workflows.

Resetting

The ever-versatile git reset can also be used to move the HEAD reference.

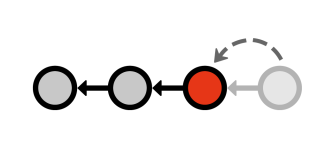

git reset HEAD~1

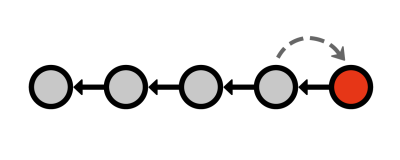

The HEAD~1 syntax parameter specifies the commit that occurs immediately before HEAD (likewise, HEAD~2 refers to the second commit before HEAD). By moving the HEAD reference backward, you're effectively removing the most recent commit from the project's history.

HEAD to HEAD~1 with git resetThis is an easy way to remove a couple of commits that veered off-topic, but it presents a serious collaboration problem. If other developers had started building on top of the commit we removed, how would they synchronize with our repository? They would have to ask us for the ID of the replacement commit, manually track it down in your repository, move all of their changes to that commit, resolve merge conflicts, and then share their "new" changes with everybody again. Just imagine what would happen in an open-source project with hundreds of contributors...

The point is, don't reset public commits, but feel free to delete private ones that you haven't shared with anyone. We'll revisit this concept later on in this session.

Reverting

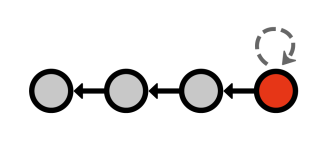

To remedy the problems introduced by resetting public commits, Git developers devised another way to undo commits: the revert. Instead of altering existing commits, reverting adds a new commit that undoes the problem commit:

git revert <commit-id>

This takes the changes in the specified commit, figures out how to undo them, and creates a new commit with the resulting changeset. To Git and to other users, the revert commit looks and acts like any other commit-it just happens to undo the changes introduced by an earlier commit.

This is the ideal way of undoing changes that have already been committed to a public repository.

Amending

In addition to completely undoing commits, you can also amend the most recent commit by staging changes as usual, then running:

git commit --amend

This replaces the previous commit instead of creating a new one, which is very useful if you forgot to add a file or two. For your convenience, the commit editor is seeded with the old commit's message. Again, you must be careful when using the --amend flag, since it rewrites history much like git reset.

This lesson represents a chapter from Git Succinctly, a free eBook from the team at Syncfusion.

Comments